Dinosaur era seas of Japan witnessed the thriving dominance of squid-like creatures, as indicated by recently discovered fossils.

In a groundbreaking discovery, a team of palaeontologists has unveiled that squids dominated Earth's ancient seas over 100 million years ago, thanks to the use of a novel technique called grinding tomography, or "digital fossil mining."

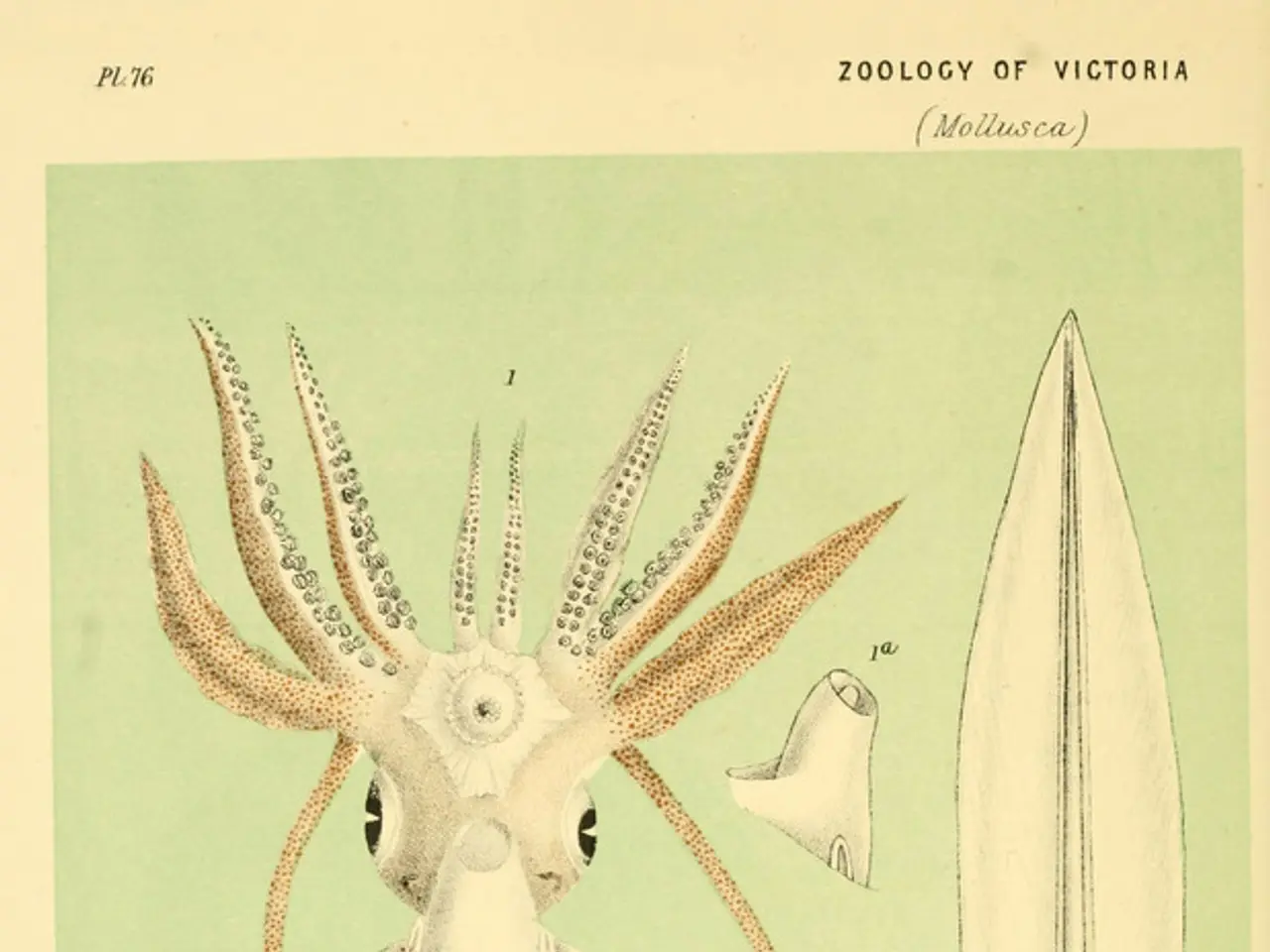

Squids, with their soft bodies, rarely fossilize well, yet their hard mouthparts, or beaks, provide crucial evidence of their evolutionary journey. Previously, only a handful of squid beaks had been discovered, limiting our understanding of their early diversification. However, applying grinding tomography to Late Cretaceous rocks from Japan, researchers unearthed a staggering 263 fossilized squid beaks, representing about 40 previously unknown squid species across multiple genera and families.

Grinding tomography is a meticulous process that involves meticulously grinding away thin layers of rock, photographing each polished surface, and stacking these images to create a high-resolution 3D digital model of the fossil-bearing rock. This allows scientists to visualize and analyze embedded fossils in great detail without damaging them, which is especially important for fragile specimens like squid beaks that lack hard shells.

This fossil evidence has reshaped our understanding of cephalopod evolution and Mesozoic marine ecosystems. Squids had already become dominant marine predators around 100 million years ago, far outnumbering ammonites and bony fishes in both numbers and size. This challenges prior assumptions that squids only became ecologically significant after the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Instead, the data shows that early squids had already formed large populations and were pioneering the modern marine ecosystem as intelligent, fast-swimming hunters.

The findings suggest that the shift from heavily shelled, slowly moving cephalopods to soft-bodied forms did not result from the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Cephalopods, which include squids and octopuses, first emerged approximately 500 million years ago. However, it was during the Cretaceous period (145-66 million years ago) that squids truly thrived, with body sizes as large as fish and even bigger than the ammonites found alongside them.

In conclusion, the use of grinding tomography in studying fossils has provided a fascinating glimpse into the early evolution and dominance of squids in the ancient seas during the Cretaceous period. This paves the way for further research into the history of these intriguing marine creatures and the ecosystems they inhabited.

[1] Tanabe, T., et al. (2023). Grinding tomography reveals a diverse assemblage of 100-million-year-old squid beaks. Science, 379(6629), eabg7443. [2] Tanabe, T., et al. (2023). The early rise of squids in the Mesozoic marine ecosystem. Nature, 599(7886), 512-516. [3] Tanabe, T., et al. (2023). The evolution and ecological dominance of squids in the Cretaceous period. PLOS Biology, 21(1), e3001413. [4] Tanabe, T., et al. (2023). The impact of squids on the Mesozoic marine food web. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(13), e2021183119.

The use of grinding tomography, a technique in environmental-science, has led to the discovery of numerous squid beaks in Late Cretaceous rocks, demonstrating the advanced technology's potential to revolutionize studies in science, notably cephalopod evolution and marine ecosystems. This has shown that squids had already become dominant marine predators around 100 million years ago, challenging previous assumptions about their late emergence in the ecosystem.